Reconstructing Arctic History

Scientists build a new database to depict Arctic sea ice variations back to 1850

There's little doubt that Arctic sea ice is shrinking, but a new study looking back to the 1850s reveals that today's ice loss is unprecedented in extent and rate. To understand what’s happening with the Arctic ice pack, scientists need access to as much data as they can get their hands on. But reliable satellite data on the frozen north extends back only to 1978 and most historical sources cover only the twentieth century. John Walsh, Chief Scientist at the International Arctic Research Center with the University of Alaska Fairbanks, knew they could do better. “We knew there was useful information out there that goes back into the 1800s,” he says. “We wanted to provide some benchmarks so we could place the retreat we’ve seen in Arctic sea ice in a longer context.”

Other scientists wanted to do the same. Walsh heard from climate change modelers who needed more information to reconstruct the Arctic’s atmospheric history. So, Walsh went to NOAA with a proposition: To make a data product that could be used by modelers to characterize sea ice back to 1850. And a natural partner for building this database was the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), part of CIRES, where a small team funded by NOAA was already experienced in using data from sources such as the military and old charts and maps to create a more robust picture. The final product, “Gridded Monthly Sea Ice Extent and Concentration, 1850 Onward," is described in a paper out in the July issue of Geographical Review.

This data set expands on an earlier product that begins in 1901. “We wanted to extend and improve on the data we already had,” says CIRES' Florence Fetterer, the NOAA liaison at NSIDC. “So we gathered historical sources of sea ice information and filled spatial and temporal gaps using an analog method.”

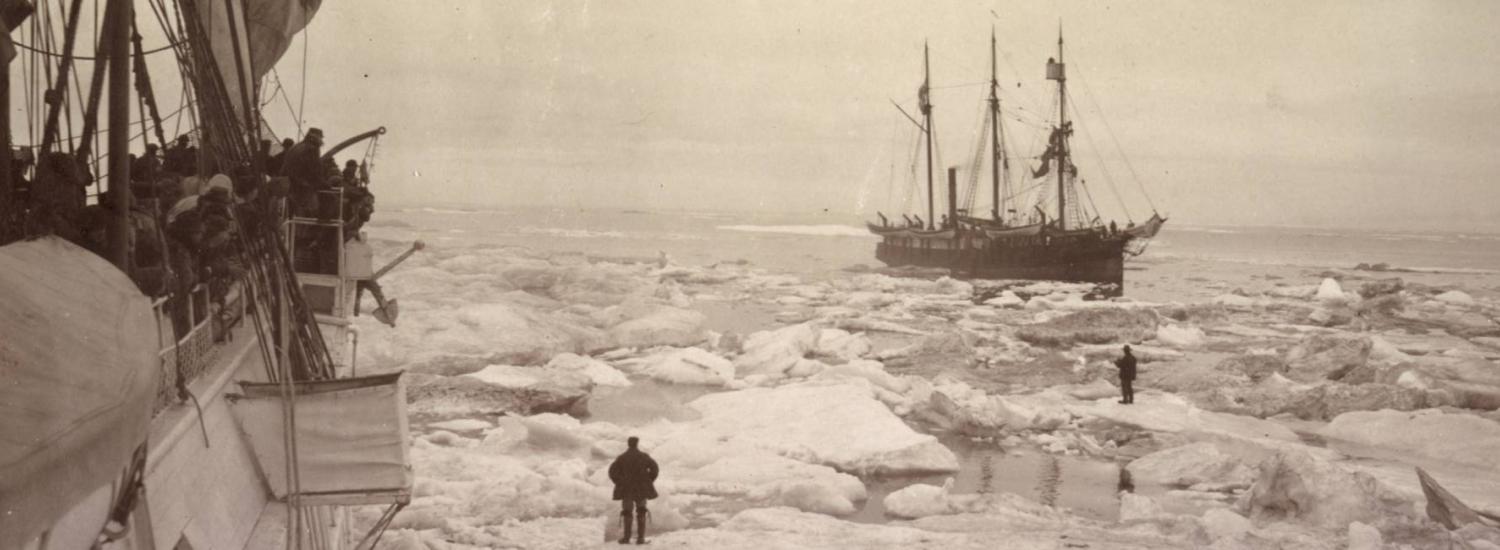

The team pulled information from fourteen historical sources, ranging between 1850 and 1978. They included Arctic sea ice charts from the Danish Meteorological Institute, compliations by U.S. Navy oceanographers, whaling ship log books, a former consulting company’s ice charts of waters around Alaska and Scandinavian ice edge data. Information from all of these sources had to be digitized and then synthesized to be compatible with one another.

Arctic Sea Ice Charts from Danish Meteorological Institute

Those steps proved challenging enough but the team also had to contend with “missing” data––times for which there was no information available. For each point with no data in a specific month and year, and no data in the surrounding months, the month and year were compared with the calendar months and years to select the best analogs. So, as an example, if they couldn’t find data for a particular region from May 1918, and there was no data from either April or June of that year either, they looked for data from all the other Mays to find the closest matches in areas that did contain data. The data from the best of those matches then served as the stand-in data for the missing region from May 1918.

The results of all this work definitively show that the Arctic ice pack is shrinking. “We looked at the extremes back to 1850,” says Fetterer. “There’s been nothing like what we’ve seen in recent years.” In addition, the rate of retreat is also unprecedented in the historical record. There have been some regions where ice loss is less, such as the Bering Sea, but overall, Arctic ice as a whole has seen a rapid decline. “People have been recording ice conditions and putting analyses into charts for a long time—a century and a half,” says Walsh. “It’s nice to fit it all into a big picture so we can place the ice retreat into a longer perspective.”