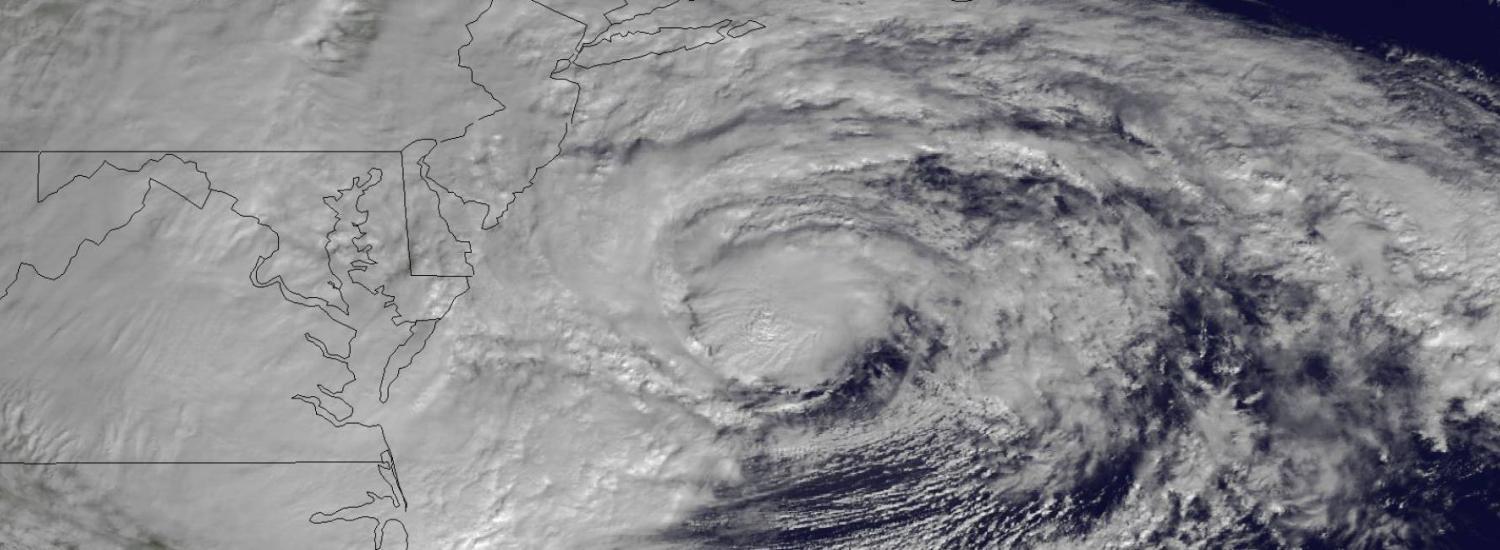

Remapping The New Jersey Coast After Hurricane Sandy

New coastal models developed by NOAA will guide future storm prediction

Two years ago, Hurricane Sandy made landfall along the U.S. East Coast, and the storm’s strong winds and waves altered the shoreline and the seafloor. The New York metropolitan region got hit especially hard. Suddenly, our coastal elevation models were no longer accurate. Emergency planners need up-to-date models, though. Small features on the seafloor and shoreline can dictate where sea water may surge in and where flood water may flow during storms.

Belmar, New Jersey. "Before" image captured by Google; "After" image captured by NOAA's National Geodetic Survey.

Now, federal and Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) researchers from NOAA’s National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC) in Boulder, Colorado, are updating detailed elevation models of the coast, above and below the waterline, in areas transformed by Hurricane Sandy, from the Delaware Bay to the Eastern tip of Long Island. First up is the New Jersey coast.

“We’re using funds made available by Congress after Hurricane Sandy to develop our capability to prepare for and respond to future events,” said Barry Eakins, a CIRES marine geophysicist and science lead for the NGDC team producing the new coastal elevation models.

CIRES/NGDC scientist Barry Eakins collecting GPS survey points on Long Island, NY in April, 2014 in support of Sandy coastal modeling. GPS data are used to validate airborne lidar measurements. (Credit: Barry Eakins, CIRES)

This work is funded by the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013, which includes money for NOAA to map and model coastal areas impacted by the hurricane. For NGDC, the end product will be updated digital elevation models or DEMs, which will help coastal planners, emergency managers and communities better prepare for storm surges, flooding, and property damage the next time a storm like Sandy hits. The DEMs, which depict New Jersey’s coastal and offshore environment, are under review and will be made available to the public within the next year.

To make a good model, scientists need accurate measurements of both land topography and underwater topography, or bathymetry. Those measurements are taken from land, air and sea. From the air and on the ground, lidar, or light detection and ranging, uses laser pulses to determine elevations on land and in shallow water. In deeper water, ship-based sonar uses sound pulses to measure water depth and map out surface features on the seafloor. “We integrate these two data sources—high resolution data near shore and lower resolution data offshore—to form more precise models,” said Susan McLean, chief of theMarine Geology and Geophysics Division at NGDC, the group in charge of making the new coastal models.

Draft image of the combined DEM tiles, merging bathymetry and topography, for the New Jersey coast and Delaware Bay. (Credit: NOAA NGDC)

For the updated New Jersey coastal DEMs, the land and sea data were supplied and processed by various NOAA offices and partner agencies:

- The NOAA Office of Coast Survey collected sonar data on the new shape of the sea floor.

- The NOAA National Geodetic Survey’s Remote Sensing Division surveyed the shoreline using lidar, focusing on the part of the coast where the land meets water.

- The NOAA Office for Coastal Management compiled land and near-shore lidar measurements from various sources.

- The NOAA Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Servicesstandardized elevation measurements from various sources.

- The U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers provided other key models and data, including changes to the land after the hurricane and additional bathymetric data.

Incorporating these data, the models depict New Jersey’s coast from the land into the ocean, giving scientists and others the tools they need to accurately forecast the impacts of storms, including coastal flooding. And having these new detailed coastal DEMs will allow researchers to update the models much more quickly after future storms, said McLean.