Mining Climate Models for Seasonal Forecasts

New study: Existing climate models useful in forecasting, model testing

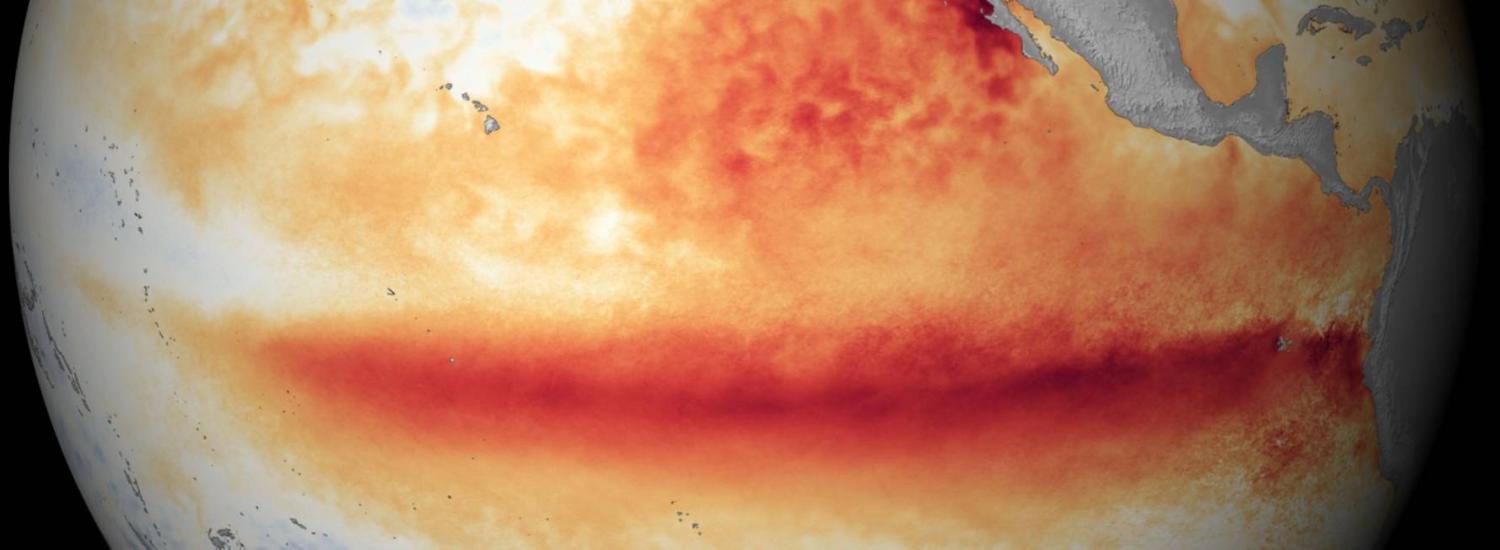

A team of CIRES and NOAA scientists has figured out a shortcut way to produce skillful seasonal climate forecasts with a fraction of the computing power normally needed. The technique involves searching within existing global climate models to learn what happened when the ocean, atmosphere and land conditions were similar to what they are today. These “model-analogs” to today end up producing a remarkably good forecast, the team found—and the finding could help researchers improve new climate models and forecasts of seasonal events such as El Niño.

“It’s a big data project. We found we can mine very useful information from existing climate models to mimic how they would make a forecast with current initial conditions,” said Matt Newman, a CIRES scientist working in NOAA’s Physical Sciences Laboratory and co-author of the study published today in Geophysical Research Letters.

Scientists typically make seasonal forecasts by observing the current global conditions, plugging that estimate into a climate model, and then running the model’s equations forward in time several months using supercomputers. These computationally intensive calculations can only be done at a few national forecast centers and large research institutions.

However, scientists use similar computer models for long simulations of the Earth’s pre-industrial climate. Those model simulations—and there are many—already exist and are freely available to anyone doing climate change studies. Newman and his colleagues decided they would try developing seasonal forecasts from these existing climate model simulations, instead of making new model computations.

Hui Ding, the paper’s lead author and also a CIRES scientist working in NOAA’s Physical Sciences Laboratory, wrote a computer program that searched the huge database of climate model simulations to find the best matches to the current observed ocean surface conditions in a given region of interest. To get the seasonal forecast, the researchers tracked how these model-analogs evolved within the simulation over the next several months.

They found that the model-analog technique was as skillful as more traditional forecasting methods. This means that long-existing climate model simulations are useful as an independent way to produce seasonal climate forecasts, including seasonal El Niño-related forecasts. “Instead of relying only on sophisticated forecast systems to forecast El Niño, we can mine these model runs and find good enough analogs to develop a current forecast,” he said.

Researchers can also use this technique to test models during the development phase. “They can look at how well forecasts from these new models compare to forecasts from pre-existing climate models matched for current conditions. That’s a quick test to see if the new models are improved,” Newman said.