What happens in the tropics can reach the Arctic and set up extreme precipitation events

NSIDC team discovering links between atmospheric rivers and rain in Arctic

In April 2016, a warm front approached southwest Greenland, causing air temperatures in the capital city of Nuuk and the surrounding area to increase rapidly. A cold front formed nearby and the two air masses collided, creating a steep pressure gradient in the atmosphere that helped funnel moisture in from the Atlantic Ocean. And then, heavy rain fell on the early spring snowpack—and slush avalanches began.

More than 800 slush avalanches were triggered by the 2016 mid-April rain on snow event in southwestern Greenland. An unmanned surface observation station was destroyed during the event, on the day with the warmest temperatures and largest amount of rain.

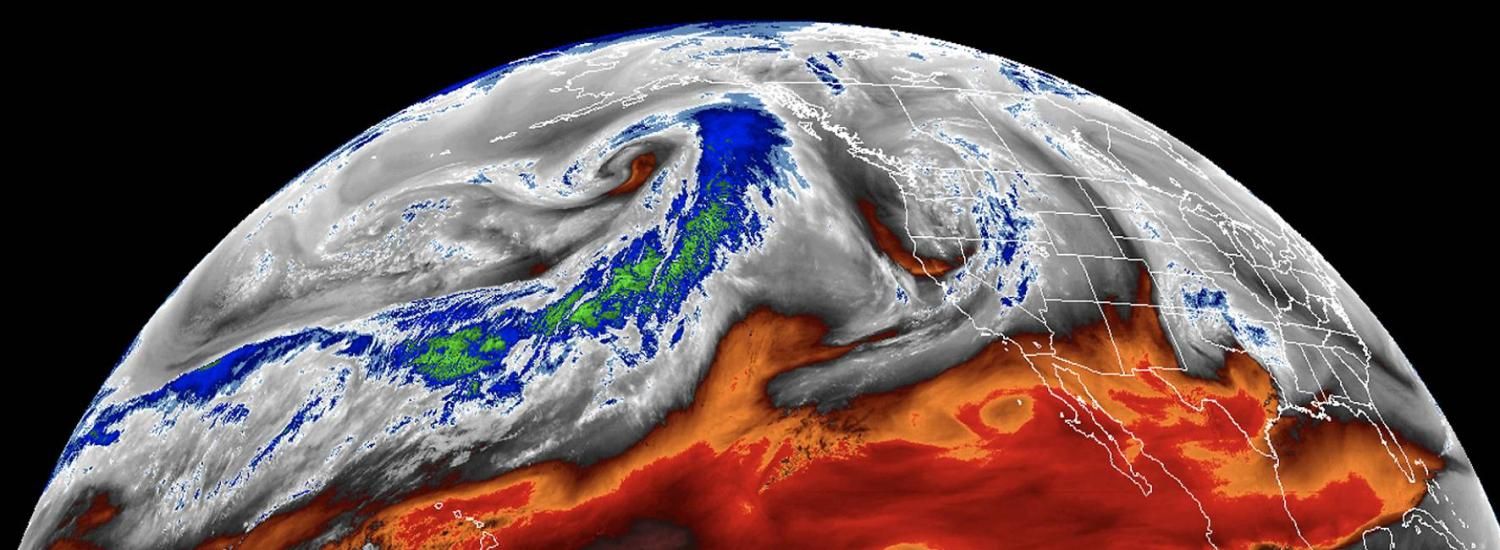

A similar set of circumstances led to a rain on snow event in Svalbard in 2012. Heavy rain from an atmospheric river, a long, narrow corridor of water vapor in the atmosphere, triggered avalanches and disrupted air travel. Then temperatures dropped and ice formed on top of the snow, and reindeer were left without access to their food beneath the snow.

So, why do these extreme precipitation events happen? And where does all the moisture come from? The answers can’t always be found in the Arctic.

“Over the past winter, people have become more familiar with atmospheric rivers. We’ve seen the effects over California,” said Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) and project lead for the Arctic Rain on Snow Study (AROSS). “But we’re only beginning to uncover the links between atmospheric rivers and extreme precipitation events in the Arctic.”

Now, the AROSS team is uncovering how meteorological phenomena connected to the tropics and subtropics, like atmospheric rivers, lead to rain on snow and other extreme precipitation events in the Arctic, and how these impact wildlife and people.

Read more from NSIDC here.