US defines outer limits of its continental shelf, making discoveries in the process

CIRES scientists were instrumental in the effort to determine the full extent of the U.S. extended continental shelf

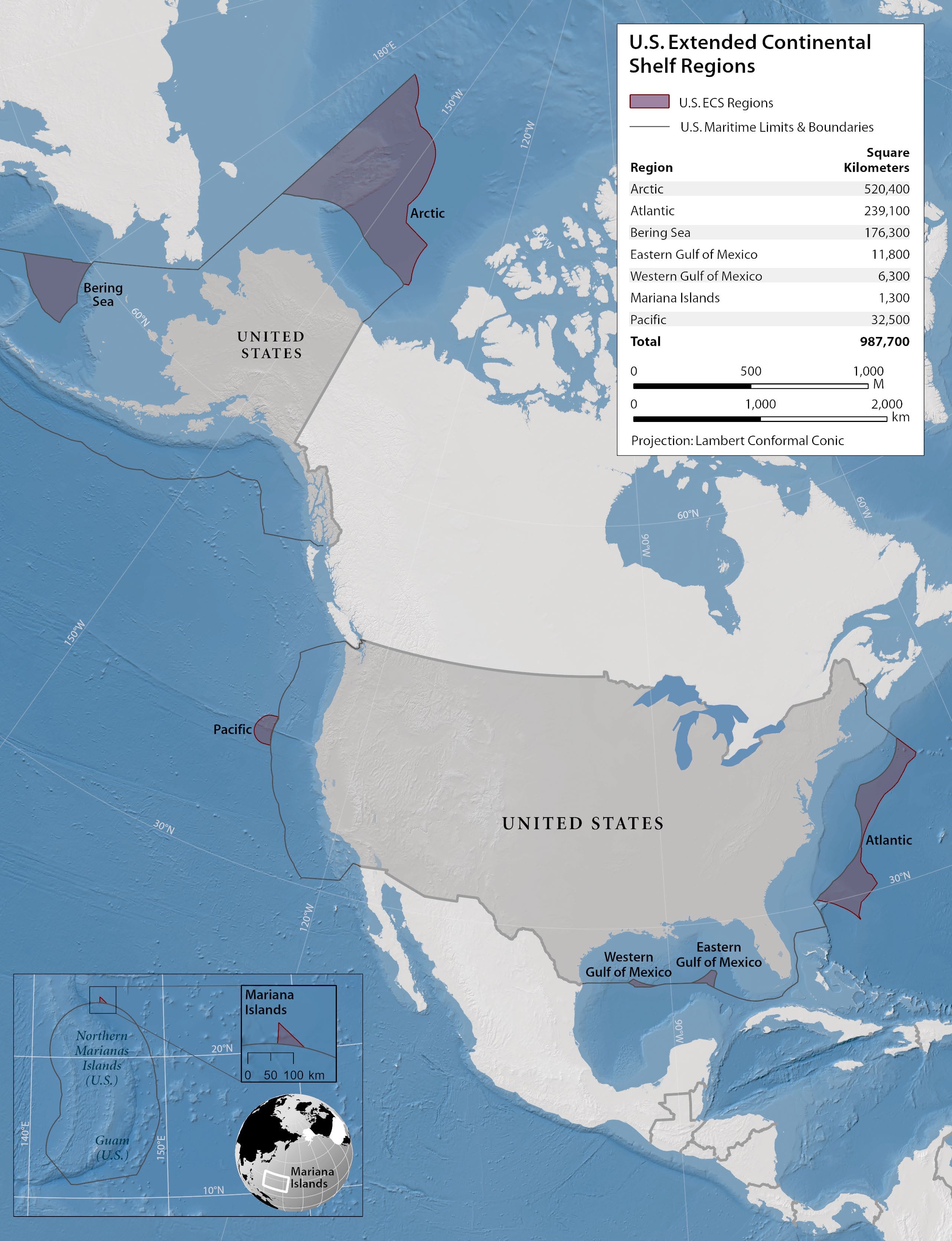

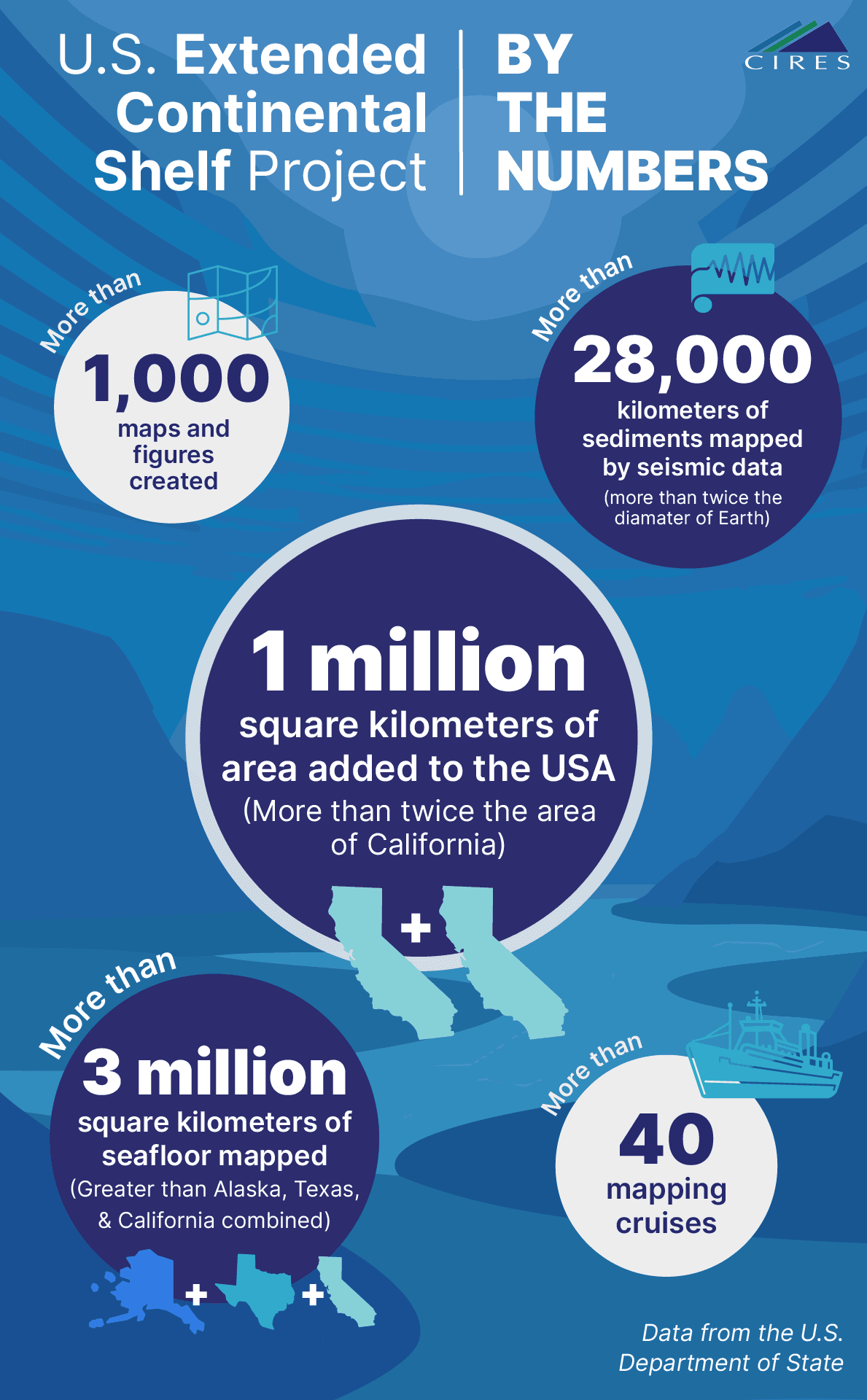

The United States has gained sovereign rights over a million square kilometers of seafloor in areas located more than 200 nautical miles from its coasts, thanks to a government-led project to define the limits of the U.S. extended continental shelf (ECS) that culminated in December 2023.

Besides adding a million square kilometers of seafloor to the United States — an area roughly twice the size of California — the project led to discoveries of interesting undersea features, including a nearly 400-kilometer-long landslide in the Atlantic Ocean and a 1,400-meter-high methane plume off the California coast.

More than 300 people across 14 federal agencies participated in the ECS project, with CIRES scientists taking the lead on analyzing the geophysical data collected by NOAA, USGS, and the University of New Hampshire. The ECS Project Office, located at NOAA in Boulder, Colorado, used those analyses to determine and document the U.S. ECS outer limits.

“We've established the limits of the U.S. continental shelf and it's now up to us to explore, learn new science, and then steward, manage, and help preserve these areas for future generations,” said Barry Eakins, a marine geophysicist working in NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) who led the CIRES ECS team.

A collaborative effort

The U.S. Department of State announced the outer limits of the U.S. ECS in December 2023, which were determined by the ECS Project Office, more than 20 years after the project began. The data collected provides researchers with maps of never-before-seen areas of the seafloor, opening the door for scientific exploration of these areas.

“This project is interesting because it's part policy, part law, part science, part operations and data collection, part geology and geophysics, part GIS analysis and cartography, and part data management,” said Brian Van Pay, director of the ECS Project Office within the U.S. Department of State.

Kevin Baumert, a lawyer with the U.S. Department of State and Legal Counsel for the ECS Project Office, said the most rewarding part of the project for him was working with a team of talented experts across different disciplines on a matter of long-term, national importance.

“We had an incredible interagency team, and I think everyone involved is proud of having defined U.S. continental shelf limits that are scientifically and legally sound,” Baumert said.

What is the extended continental shelf?

In geologic terms, continental shelves are the edges of continents that are submerged under the ocean. This physical shelf is part of the continental margin, which also includes the continental slope and rise that lie between the shelf and the deep ocean floor.

Legally speaking, the continental shelf is the extension of a country’s land territory under the sea. The portion of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the coast is called extended continental shelf.

Government officials began planning to map and define areas where they suspected the U.S. had ECS in the early 2000s. The ECS Project Office used the rules laid out in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea to determine the ECS outer limits, which require knowledge of the shape and depth of the seafloor and the thickness of sediments. Data collection began in 2003 and involved mapping the seafloor topography to define where the physical continental shelf and slope end and determining sediment thickness in some areas.

Defining limits and making discoveries

NOAA, with help from CIRES scientists, led the effort to collect the seafloor topography data, while USGS took the lead in determining the sediment thickness. Over the course of the project, NOAA mapped more than three million square kilometers of seafloor in U.S. coastal areas. In total, it’s an area larger than Alaska, California, and Texas combined; it was the largest seafloor mapping effort the United States has ever undertaken.

With their expertise in marine geophysics, data management, GIS, and cartography, CIRES researchers at NOAA’s NCEI led the effort to analyze the data collected. The monumental task involved evaluating all three million square kilometers of newly mapped seafloor, interpreting the geologic features in certain key areas, and managing and archiving the gigantic amount of data produced.

One challenge the team faced was determining whether certain seafloor features, like sediment fans, are part of the continental slope or not.

“It's the processes that are going on on the seafloor that we're trying to understand to help us determine if what we're seeing is a feature of the continental slope or a feature of the continental rise or deep ocean floor,” Eakins explained.

The U.S. Department of State and NOAA established the ECS Project Office in 2014 and since that time, it has included staff from CIRES, NOAA, and the U.S. Department of State. The Project Office collaborated with others across NOAA and USGS to determine the precise ECS limits of seven U.S. regions.

Eakins said what made the project so successful was the team’s careful attention to detail; they wanted to be confident that their results would be robust and defensible, he said.

"This is a tremendous opportunity to go out and explore the geologic features, the sediments that are down there, and the life that is down there as well.” - Barry Eakins

More than just limits

Determining the ECS limits helps scientists understand the geologic history of remote areas of the seafloor and contributes much-needed data to the ongoing international effort to map the entirety of Earth’s seafloor by 2030.

The mapping efforts also revealed some interesting features of the seafloor. Researchers determined the precise depth of the Challenger Deep — the deepest spot in the ocean — at 10,994 meters (36,070 feet). In the Arctic Ocean, researchers mapped scrapes on the seafloor made by glaciers and pockmarks made by exploding gas. It is now up to scientists to explore these areas.

“The United States has established the limits of the seafloor that it has sovereign rights to, and that seafloor is still largely unknown,” Eakins said. “So this is a tremendous opportunity to go out and explore the geologic features, the sediments that are down there, and the life that is down there as well.”